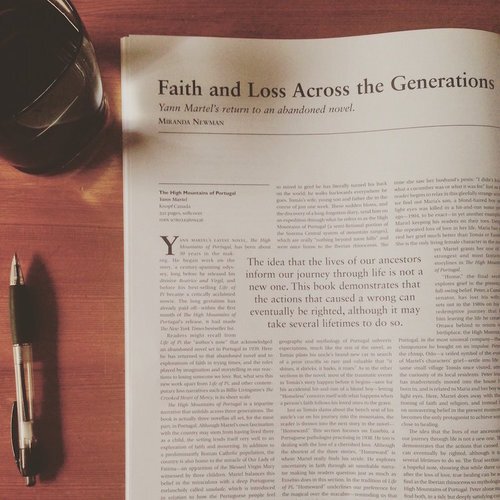

Faith and loss across the generations

Yann Martel’s latest novel, The High Mountains of Portugal, has been about 30 years in the making. He began work on the story, a century-spanning odyssey, long before he released his divisive Beatrice and Virgil, and before his best-selling Life of Pi became a critically acclaimed movie. The long gestation has already paid off—within the first month of The High Mountains of Portugal’s release, it had made The New York Times bestseller list.

Readers might recall from Life of Pi the “author’s note” that acknowledged an abandoned novel set in Portugal in 1939. Here he has returned to that abandoned novel and to explorations of faith in trying times, and the roles played by imagination and storytelling in our reactions to losing someone we love. But, what sets this new work apart from Life of Pi, and other contemporary loss narratives such as Billie Livingston’s The Crooked Heart of Mercy, is its sheer scale.

The High Mountains of Portugal is a tripartite narrative that unfolds across three generations. The book is actually three novellas all set, for the most part, in Portugal. Although Martel’s own fascination with the country may stem from having lived there as a child, the setting lends itself very well to an exploration of faith and mourning. In addition to a predominantly Roman Catholic population, the country is also home to the miracle of Our Lady of Fatima—an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary witnessed by three children. Martel balances this belief in the miraculous with a deep Portuguese melancholy called saudade, which is introduced in relation to how the Portuguese people feel about the Iberian rhinoceros: “It was hunted and hounded to extinction and vanished, as ridiculous as an old idea—only to be mourned and missed the moment it was gone.” In a setting rich with mythology and malaise, Martel is able to explore loss in three protagonists’ lives through varying lenses of belief in a place that most allows for it.

The first story, “Homeless,” opens in 1904 and follows Tomás, a museum employee from Lisbon so mired in grief he has literally turned his back on the world; he walks backwards everywhere he goes. Tomás’s wife, young son and father die in the course of just one week. These sudden blows, and the discovery of a long-forgotten diary, send him on an expedition through what he refers to as the High Mountains of Portugal (a semi-fictional portion of the Sistema Central system of mountain ranges), which are really “nothing beyond mere hills” and were once home to the Iberian rhinoceros. The geography and mythology of Portugal subverts expectations, much like the rest of the novel, as Tomás pilots his uncle’s brand-new car in search of a prize crucifix so rare and valuable that “it shines, it shrieks, it barks, it roars.” As in the other sections in the novel, most of the traumatic events in Tomás’s story happen before it begins—save for his accidental hit-and-run of a blond boy—letting “Homeless” concern itself with what happens when a person’s faith follows his loved ones to the grave.

Just as Tomás slams about the bench seat of his uncle’s car on his journey into the mountains, the reader is thrown into the next story in the novel—“Homeward.” This section focuses on Eusebio, a Portuguese pathologist practising in 1938. He too is dealing with the loss of a cherished love. Although the shortest of the three stories, “Homeward” is where Martel really finds his stride. He explores uncertainty in faith through an unreliable narrator making his readers question just as much as Eusebio does in this section. In the tradition of Life of Pi, “Homeward” underlines our preference for the magical over the macabre—reminding us that sometimes it is better to accept a fantastical version of trying events than to live with their truths.

Even the novel’s secondary characters are not immune to grief. As Eusebio works through the New Year, a widow visits him from the mountains. She has not come alone. She has hauled her husband’s corpse down the mountain in a suitcase. Eusebio quickly discovers this is an atypical autopsy, as he opens the body to find, among other things, a flute, mud, coins and a lifeless chimpanzee holding a small dead bear cub. As he works, Maria tells him the story of her marriage even detailing the first time she saw her husband’s penis: “I didn’t know what a cucumber was or what it was for.” Just as the reader begins to relax in this gleefully strange scene, we find out Maria’s son, a blond-haired boy with light eyes was killed in a hit-and-run some years ago—1904, to be exact—in yet another example of Martel keeping his readers on their toes. Despite the repeated loss of love in her life, Maria has carried her grief much better than Tomás or Eusebio. She is the only living female character in the novel, yet Martel grants her one of the strongest and most fantastical storylines in The High Mountains of Portugal.

“Home,” the final section, explores grief in the presence of full-swing belief. Peter, a Canadian senator, has lost his wife. He sets out in the 1980s on his own redemptive journey that finds him leaving the life he created in Ottawa behind to return to his birthplace, the High Mountains of Portugal, in the most unusual company—that of a chimpanzee he bought on an impulse. Peter and the chimp, Odo—a veiled symbol of the evolution of Martel’s characters’ grief—settle into life in the same small village Tomás once visited, attracting the curiosity of its local residents. Peter learns he has inadvertently moved into the house he was born in, and is related to Maria and her boy with the light eyes. Here, Martel does away with the questioning of faith and religion, and instead focuses on unwavering belief in the present moment. Peter becomes the only protagonist to achieve something close to healing.

The idea that the lives of our ancestors inform our journey through life is not a new one. This book demonstrates that the actions that caused a wrong can eventually be righted, although it may take several lifetimes to do so. The final section ends on a hopeful note, showing that while there can be life after the loss of love, true healing can be as hard to find as the Iberian rhinoceros so mythologized in the High Mountains of Portugal. Peter alone manages to find both, in a tidy but deeply satisfying conclusion.

Although he explores the role of faith in grieving through three similar male characters, Martel’s grasp on voice allows for distinct and unique personalities to emerge in each section of the book. The reader is drawn into each protagonist’s life just long enough to get his message across before meeting the next. Martel places the fates of his characters entirely in their own hands. He colours each story with varying levels of belief and lets the characters lead us through their sorrows in a thrilling and winding read that charts the evolution of grieving.